The T.A.M.I. Show: Soul Superstars Shatter Race Barriers 50 Years Ago

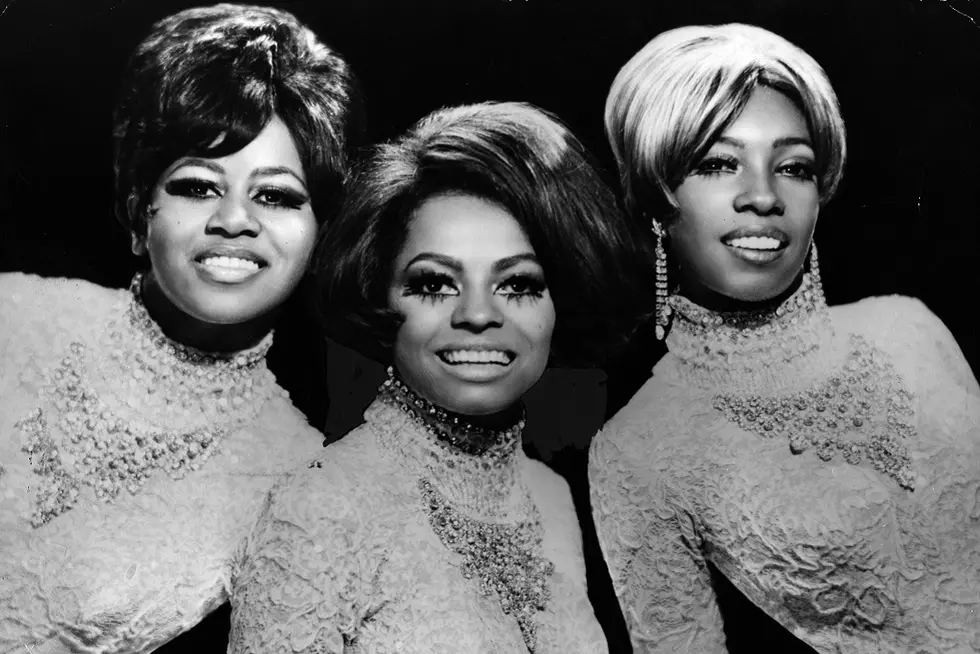

The T.A.M.I. show, filmed at California's Santa Monica Civic Auditorium on October 28 and 29, 1964, featured a remarkable array of talent that included Marvin Gaye, Diana Ross and the Supremes, Smokey Robinson and the Miracles, Chuck Berry and James Brown. Fifty years later, the event is considered one of the greatest concerts ever staged.

T.A.M.I., an acronym for Teenage Awards Music International, was filmed both days and the October 29 performances were selected for the film. The largely white audience members were teens from Santa Monica high schools.

Producer Bill Sargent intended the show to be an annual event. Fans would vote for their favorite artists and money would go to help teens “establish a position of respect in their communities, and in our total society.”

Those plans were scuttled when the film’s distributor, American International Pictures, took control of the film when Sargent could not meet mounting expenses.

Released in theaters December 29, 1964, the concert was groundbreaking for its racially integrated lineup of stars. The soul and R&B stars were joined by hosts Jan and Dean, the Beach Boys, the Barbarians and Lesley Gore. From the UK came the Rolling Stones, Gerry & the Pacemakers and Billy J. Kramer & the Dakotas.

“The best part was that everybody was there for everybody else. Nobody was treated like the star,” director Steve Binder told the Santa Barbara Independent. “They called it chemistry, but I think it was because all the acts stayed there for the whole two days.”

On the show's DVD release, Binder's commentary includes memories of some of the stars:

Chuck Berry: “One of the funniest things that happened before we even started filming T.A.M.I. was that Chuck Berry refused to go out on stage until he got paid in cash or a money order. And Sargent pulled a rabbit out of a hat on a Sunday and he got Hank Saperstein and Harold Goldman, who owned two big companies and were friends of his, to give him the cash to pay Chuck Berry. And that was a real miracle.”

Smokey Robinson and the Miracles: “In those days, when we did T.A.M.I., I don’t think the white youth audience ever saw these incredible artists performing. A lot of them had heard their records but nobody saw the Miracles with Smokey on stage performing these songs. And I think it blew a lot of people away and it helped to integrate the whole rock ‘n’ roll world. It no longer was homogenous where black artists had to be in the shadows.”

Marvin Gaye: “Marvin, when he became famous, fought doing anything the commercial way as far as what was stereotyped as ‘success’ in the music business. Marvin always strove to break ground and do things his way. He was the complete package, as a writer, producer… his later records are masterpieces.”

Binder struggled to decide who would close the show: James Brown, “The Hardest Working Man in Show Business,” or the British Invasion’s Rolling Stones, who had just scored their first U.S. hit with ‘Time Is On My Side.’

“I can’t tell you now why I wanted the order that way,” Binder recalled in ‘The One: The Life and Music of James Brown.’ “But then, I didn’t hear any first-person resistance to the idea, other than from James.

“I think how it came down was, he said, ‘I am the final act on the bill, right?’ And I said no. And he said, ‘Nobody follows me.’

“‘Actually,’ I said, ‘we’ve got the Rolling Stones.’ He didn’t care – he was so confident in himself.”

Brown delivered an 18-minute tour de force that included ‘Out of Sight,’ ‘Prisoner of Love,’ ‘Please, Please, Please’ and ‘Night Train.’ His performance presented a special challenge for the director. “Everyone had about a half hour to rehearse before we filmed them,” Binder told Esquire. “I barely knew who James Brown was when I went up to speak to him. The first thing he said to me was, ‘I don't rehearse! You'll know what to do with the camera when you see me.’ I was petrified. Somehow, I managed to capture his amazing moves. To this day, I don't know how. It was God-given, I guess.”

“As each act went on, we watched with the other artists backstage in a big viewing room, yelling encouragement and cheering,” Stones bassist Bill Wyman wrote in ‘Bill Wyman: Stone Alone.’ “During an incredible set from James Brown and his Famous Flames, all the acts went as crazy as the audience out front. We now knew what James Brown meant and were petrified at the prospect of following him. But in our dressing room, Chuck Berry and Marvin Gaye, who shared with us, were very encouraging. Marvin told us: ‘People love you because of what you do on stage, so just go out there and do your thing – that’s what I do.’”

Watch Diana Ross and The Supremes Perform on the T.A.M.I. Show

In his autobiography ‘James Brown: The Godfather of Soul’ the late singer described his performance:

“We went on, a little nervous because we didn’t think this audience really knew us, but when we went into ‘Out of Sight,’ they went straight up out of their seats. We did a bunch of songs, nonstop, like always. For our finale we did ‘Night Train.’ I don’t think I ever danced so hard in my life, and I don’t think they’d ever seen a man move that fast. When I was through, the audience kept calling me back for encores. It was one of those performances when you don’t even know how you’re doing it. At one point during the encores I sat down underneath a monitor and just kind of hung my head, then looked up and smiled. For a second I didn’t really know where I was.

“The Stones had come out in the wings by then, standing between all those guards. Every time they got ready to start out on the stage, the audience called us back. They couldn’t get on – it was too hot out there.”

The high point of the show is Brown’s electrifying ‘Please, Please, Please.’ Overcome with emotion, Brown repeatedly falls to his knees. He is helped up by aide Danny Ray, who drapes a robe over Brown’s shoulders and tries to escort him off stage. But time and again, Brown rebuffs Ray, throws off the robe and launches back into the song.

“See the emotion on his face?” Binder noted in his commentary. “He’s not just singing, he is acting. He’s telling you everything that he wants you to know about what he’s singing about.”

“I tell you, it’s a masterpiece and the beginning of my career in one way,” Brown said of the show in the L.A. Times. “It was great for me. I’d been getting that kind of response for a long time, but white people didn’t get a chance to see me because they didn’t go to the venues I was playing at.”

More From HOT 99.1